[JS] Promise Objects and Promise Methods

April 23, 2021

What is a Promise?

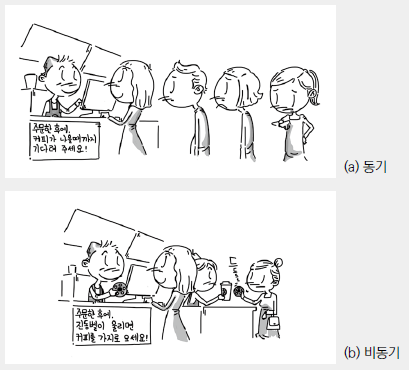

The above diagram illustrates synchronous and asynchronous operations. Asynchronous allows other tasks to be performed while waiting for data to be requested and received.

The above diagram illustrates synchronous and asynchronous operations. Asynchronous allows other tasks to be performed while waiting for data to be requested and received.

Promise can be likened to a doorbell in this analogy. Just as a doorbell connects a shop owner and a customer, a promise in JavaScript is a special object that connects “production code” and “consumption code”. Let’s explain “production code” and “consumption code” through the following code examples.

let promise = new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

setTimeout(() => resolve('done!'), 1000)

//executor, production code

})

promise.then(

(result) => alert(result),

(error) => alert(error)

//consumption code

)The result of the above code is the output of “done!” after 1 second. Let’s understand the reasons step by step.

The resolve and reject arguments of the executor are callbacks provided by JavaScript itself. Developers only need to focus on writing code inside the executor, without worrying about resolve and reject.

However, inside the executor, depending on the situation, one of the callbacks passed as arguments must be called:

resolve(value)— Called when the task is successfully completed, withvaluerepresenting the result.reject(error)— Called if an error occurs, witherrorrepresenting the error object.

The result is initially an internal property of the promise object and starts as undefined. It is then updated to value when resolve(value) is called or to error when reject(error) is called.

Returning to our analogy of the shop owner and customer, the production code (executor) is the shop owner. The completed coffee represents the result. The consumer who receives this coffee is the consumption code. And in this process, the doorbell that notifies the completion of the coffee is the Promise itself!

There is much more to promises, such as state, but let’s move on to Promise.all(), Promise.race(), and Promise.finally().

Promise.all()

const promise1 = Promise.resolve(3)

const promise2 = 42

const promise3 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 100, 'foo1')

})

const promise4 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 100, 'foo2')

})

Promise.all([promise1, promise2, promise3, promise4]).then((values) => {

console.log(values)

})

//output: Array [3, 42, "foo1","foo2"]By placing the promises to be processed in an array and passing it as an argument to Promise.all(), all the promises in the array are almost simultaneously triggered. Therefore, although promise3 and promise4 each take 1 second to resolve, they are triggered simultaneously, resulting in their output appearing after just 1 second.

One thing to note when using Promise.all() is that if any element in the array is rejected, it immediately rejects.

var p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('one'), 1000)

})

var p2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('two'), 2000)

})

var p3 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('three'), 3000)

})

var p4 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('four'), 4000)

})

var p5 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

reject(new Error('rejected'))

})

// Using .catch:

Promise.all([p1, p2, p3, p4, p5])

.then((values) => {

console.log(values)

})

.catch((error) => {

console.log(error.message)

})

// Console output:

// "rejected"In the above code, since p5 throws an error, the results of p1, p2, p3, and p4 are not output. To see the results of p1, p2, p3, and p4, handle the potential rejection beforehand.

var p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('p1_delayed_resolve'), 1000)

})

var p2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

reject(new Error('p2_immediate_rejection'))

})

Promise.all([

p1.catch((error) => {

return error

}),

p2.catch((error) => {

return error

}),

]).then((values) => {

console.log(values[0]) // "p1_delayed_resolve"

console.log(values[1]) // "Error: p2_immediate_rejection"

})In the above code, p2’s immediate rejection is handled using .catch(), so the result array contains the result of p1 and the error message from p2.

Promise.race()

Unlike Promise.all(), which receives an array of promises and returns an array of their results, Promise.race() resolves with the value of the first promise that resolves or rejects.

Think of it as a race among promises where only the result of the fastest promise is passed to the .then() clause!

var p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('one'), 1000)

})

var p2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('two'), 2000)

})

var p3 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('three'), 3000)

})

var p4 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('four'), 4000)

})

Promise.race([p1, p2, p3, p4, p5]).then((value) => {

console.log(value)

})

// Console output:

// "one"In the above code, p1 finishes execution the fastest, so only 'one' is logged to the console.

Similarly, even when an error occurs, only the error that occurs first is passed to the catch clause.

var p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => reject('one'), 1000)

})

var p2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => reject('two'), 2000)

})

var p3 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => reject('three'), 3000)

})

var p4 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => reject('four'), 4000)

})

Promise.race([p1, p2, p3, p4, p5])

.then((value) => {

console.log(value)

})

.catch((error) => {

console.log('error', error)

})

// Console output:

// error onePromise.finally()

The finally() method returns a promise. It executes a specified callback function, regardless of whether the promise is fulfilled or rejected. This provides a way to run code after a promise has been completed, regardless of whether it was successful or not.

let isLoading = true

//fetch returns a promise object

fetch(myRequest)

.then(function (response) {

var contentType = response.headers.get('content-type')

if (contentType && contentType.includes('application/json')) {

return response.json()

}

throw new TypeError("Oops, we haven't got JSON!")

})

.then(function (json) {

/* process your JSON further */

})

.catch(function (error) {

console.log(error)

})

.finally(function () {

isLoading = false

})In the above code, regardless of the result of fetch, the .finally() clause ensures that isLoading becomes false.

References: